It is probable that some reader of this post will brand me a heretic. Such is the state of things when discussing theology proper. I was reminded of this difficulty through reading James Dolezal’s All That is in God: Evangelical Theology and the Challenge of Classical Christian Theism.

It is probable that some reader of this post will brand me a heretic. Such is the state of things when discussing theology proper. I was reminded of this difficulty through reading James Dolezal’s All That is in God: Evangelical Theology and the Challenge of Classical Christian Theism.

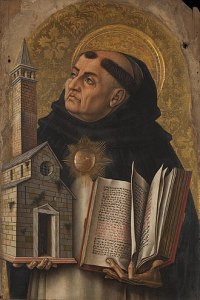

This isn’t a book review per se, but reflections on the topic of divine simplicity spurred by reading Dolezal. I am not denying divine simplicity, rather I am offering a methodological critique of the approach Dolezal takes. Divine simplicity refers to the idea that God is not composed of “parts.” What he is, he is throughout his being. We do not add up all the attributes Scripture describes and the sum of this we call God. He does not have love, he is love. He does not have justice, he is justice.

Divine Simplicity and the Challenge of Syntax

Divine simplicity is a topic that requires nuance and close reasoning. It relies on a collection of terms that are not strictly biblical, which is to say, as Dolezal acknowledges

There is no single biblical proof text for this doctrine. It follows, rather, by way of good and necessary consequence from a number of other doctrines that are clearly taught in Scripture. And though the cognitive realization of divine simplicity requires that we contemplate the implications of other doctrines, it is not for that reason any less biblical. All that is explicitly stated in Scripture and all that must necessarily follow from Scripture must equally be regarded as the Bible’s teaching.”[1]

I don’t want to attribute more to this statement than he means. Believers acknowledge that we often reason from the Scriptures to certain conclusions, but the challenge is, what is (or isn’t) a “good and necessary consequence”? Another way of asking this is, when does hermeneutics rise to a level of equal authority with revelation? And here I think Dolezal tends to go beyond what is warranted, because throughout the book, much of his appeal is to a paradigm of Aristotelianism and Thomism. He presents the logic of simplicity, but in the appeal to logic, we are now in the world of being, ontology, actuality, nature, essence, and other terms from the realm of philosophy.

The vocabulary of this is prone to misunderstanding and different definitions. This is why, as Dolezal notes, several in the Reformed tradition posit an understanding of simplicity where God interacts with his creation, yet remains ontologically immutable. For Dolezal, “every state of being whether essential or nonessential, is an ontological state.”[2] But what is essential versus nonessential in God, and where might one go for such definitions? One could claim that to speak of essential verses nonessential is itself a denial of simplicity! This is where one sees a shibboleth of Aristotelianism at work. If one doesn’t define the terms in the same way, does it mean one has strayed from orthodoxy?

God as He is, not as He has described himself

In his critique of those who get simplicity wrong, Dolezal has to explain how in some cases God’s revelation of himself in Scripture appears to contradict some of the claims of simplicity. This isn’t just a view on anthropomorphisms in Scripture. Most would agree that when the Bible speaks about the “arm of the Lord” it is not literal. God is spirit and not corporeal. It is more nuanced to explain how the attributes of God are not features or aspects of his being, but are his being. Because of how the Bible speaks of God, we are not in the habit of thinking “in Him all his attributes are really identical with each other.”[3] But this is the claim of simplicity. “As for the distinctions we make among the attributes of God, these simply follow from the accommodated and apportioned manner by which God has divulged something of the fullness of his being to finite creatures.”[4] In other words, Dolezal says the way Scripture presents God and his attributes is an accommodation to our limits, and “the distinctions we make among the attributes in our God-talk follow from the manner in which God’s perfection is revealed, not from the manner in which it exists in Him.”[5] (emphasis mine.)

Dolezal’s position recalls the famous illustration of three blind men feeling an elephant, and each one coming to a different conclusion—because none of them see the whole. But, Tim Keller has identified a weakness. “This illustration backfires on its users. The story is told from the point of view of someone who is not blind. How could you know that each blind man sees only part of the elephant unless you claim to be able to see the whole elephant?”[6]

The revelation we have of God is Scripture, and whatever we learn from nature, most would agree it is less explicit than revelation. If there is a different, more accurate way of knowing and understanding how God really is, how does Dolezal know it? He is the man standing off at some distance, and seeing the whole. Or rather, Thomism and the heritage of Reformed scholasticism is that man, but the question remains: how do they know?

Is nature a reliable guide?

At a few points, Dolezal tries to explain how God cannot be a composite being, because “those things composed of parts thus depend on sources of being and actuality and actuality really distinct from and prior to themselves.”[7] We know this from nature itself, that anything composite needs someone or something to compose it. If we say this of God, we are claiming some being is prior to Him, and that is an impossibility. I agree with the conclusion, but not the reasoning.

Dolezal presents this without proof, or rather, his proof is that it simply makes sense, and is evidenced in nature. Yet God is supernatural, above nature. His being is unique, thus to look at nature for why a thing about God cannot be true might provide nothing helpful.

On the other side of this, it seems that those with whom Dolezal disagrees would be able to turn his argument around. In Romans 1:20, Paul says “For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made.” If we look at creation, we can see evidence of God’s nature. If nature shows us composite things, and the created world manifests God’s divine nature, then God must be composite. So one might argue. I am not claiming this is true, rather, I am saying it demonstrates a weakness in Dolezal’s argument.

Because divine simplicity is a derived doctrine, it faces a greater challenge to its adherents to demonstrate how it is essential in the same was as the atonement, or the deity of Christ. I am not saying I think divine simplicity is untrue. I am still studying the claims and implications of it. Indeed, I reject much of what Dolezal rejects as untrue of God. But if the primary appeal to the truth of divine simplicity rests of Aristotle and Thomism—on the logic of ontology and its sometimes abstruse vocabulary—it must have a better foundation than this. And if, as Dolezal claims, to differ from the understanding of simplicity that Reformed scholasticism has given us is to give up true religion itself, then apologists must do a far better job.

[1] James E. Dolezal, All That is in God: Evangelical Theology and the Challenge of Classical Christian Theism (Grand Rapids, Reformation Heritage Books, 2017), 44-45.

[2] Dolezal, 26

[3] Dolezal, 42.

[4] Dolezal, 71.

[5] Dolezal, 43.

[6] Tim Keller, The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism (New York, Riverhead Books, 2008), 9.

[7] Dolezal, 44.